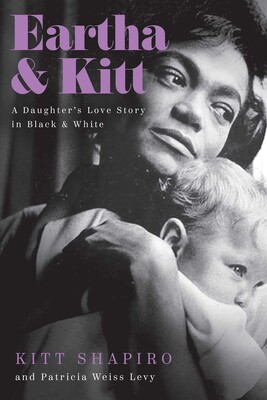

Source: Pegasus Books / Pegasus Books

Just in time for Mother’s Day, Kitt Shapiro, the daughter of the legendary and iconic Eartha Kitt has released a memoir about her life with her mother. During our interview, we discussed the ignorant comments Kitt fields as the white daughter of a famous Black mother, what people didn’t know about Eartha Kitt & how she’s being her mother’s voice now that she’s no longer here. See what she had to say below.

MadameNoire: Why did now feel like the right time to write the book about your mother?

Kitt Shapiro: I think emotionally it took time for me to come to terms with the fact that I am the way that her voice continues, in so many ways. Her films, her music and her television that all lives on but who she was as a person, I am the connection to that.

And the more that I have been out there and facing the public—not that I’m doing a huge amount—the more that I hear people leave comments that are so disappointing. I have people who say to me, ‘You can’t possibly be her daughter.’ ‘There’s no way you are her biological child because you don’t look anything like her.’ ‘Your skin’s not dark enough.’ Obviously, people don’t ever say that face to face, they only say it behind a computer. But it so speaks to how my mother felt about this desire we have as human beings to pigeon hole each other and to keep each other in these categories that keep us separate.

And because another person doesn’t behave, or look or have the same beliefs as we think they should, we then chastise them, judge them and put them down or deny that they exist.

It’s coming to a head in our society right now. The voices are getting louder and louder and the hate speech is so repulsive. I have been reluctant in my life to be like my mother-where I wasn’t one who was that outspoken. But there comes a point, an age where you’re just like screw it. You all need to have your heads examined.

So the first thing I like to say to people is, ‘In what planet do you think a Black woman could have adopted a white baby in 1961? Let’s be real.’

The sad part is that I do look like her. Genetics are a funny thing and there’s nothing I can do about that. There’s nothing anyone can do about the way they were born.

When my mother was born in 1927, in North, South Carolina, she was referred to as a yella gal because she wasn’t Black enough and in 2021, I’m told I can’t be her daughter because I’m not Black enough. And it’s so sad that this is where people have to put their efforts.

I think everyone should get a DNA test at birth and we can all see how mixed we really are. And that can be one less thing we all fight over.

MN: As a child did you internalize any of that? I know you know you’re her daughter. But did that bother you growing up?

Kitt Shapiro: No. I never even thought about it. Literally, never crossed my mom. I say that and I don’t want to sound naïve. But by the time I was born, my mother was already very famous. People are always more impressed with celebrity than they are with being prejudice.

I didn’t witness my mother’s mistreatment. I wasn’t around to see the extent of what she experienced. And I grew up in a different environment. I grew up with a mother who said, ‘I’m not pink, I’m not green, I’m not Black, I’m not white. I’m a part of the human race.’ She would say to me, ‘You are a walking United Nations. You either break every rule or you fill every quota.’

And she loved that.

I knew how much I looked like her. We used to sit in the mirror and stare and point out our features. As a little girl, that’s what you do with your mother. We have the same beauty marks in certain spots. I would often say to her, ‘God put me on this earth to be your daughter. I was supposed to be your daughter.’

My father is as lily white as they came so it never shocked me. I never thought I looked different.

Source: Pegasus Books / Pegasus Books

It wasn’t until we were in South Africa, and I was 12 years old. It was 1973-74 and it was obviously during Apartheid. My mother went there to perform for mixed race audiences and to raise money for Black children for school.

And that was the first time I remember being treated differently because of my skin tone. Even though my mother was a VIP and was allowed to go anywhere, there were a few time when the person didn’t recognize my mother and I was told I could come in and my mother was asked to leave.

In the book, I talk about this amusement park that was a white’s only park. And I was not a naïve little girl. I had traveled the world and was quite sophisticated but it never even occurred to me that my mother and I would be thought of as different until that moment.

That was really eye-opening. My mother, as I say in the book, handled it as only she could. She stood up and she left, very calmly. And I was yelling, ‘Tell them who you are. Tell them you can be here. He doesn’t know who you are. Just explain to him.’

And she looked at me and said, ‘Don’t panic. God may not be there when you want Him but He’s always on time.’

A few days later, she was doing a press conference and the photographers wanted a picture with the amusement park in the back and she made a comment, ‘It’s so funny, I was thrown out of that park the other day.’ And of course, it was a big to-do. The owner of the park found out and he was all embarrassed and upset. He said, ‘What can I do to make it up to you Ms. Kitt?’ And she said, ‘Well, I’m raising money to build schools so your money, a check would be very much appreciated. And my daughter would really like to come back with her friends.’

And he gave us the tickets and my mother brought a group of children who were all different races.

That was how she felt that you could affect change. I would have stood up and started screaming and yelling, ‘Don’t you know who I am?!’ But my mother’s methods were so much more subtle and impactful in so many ways. That to me, expressing and parlaying who she was as a human being, that strength that she had—it wasn’t about being fearless. It was about following your gut and listening to your heart and not compromising yourself for anybody else.

I think that that is so incredibly powerful and hard to do that I feel it’s important that people really understand that little tiny, 5’2 woman was such a powerhouse because she didn’t believe in doing it differently. That’s where her strength really was.

MN: I know that your mother had a very, very rough childhood, a lot of abuse, abandonment etc. How do you think that impacted the type of mother she was to you?

Kitt Shapiro: I think, luckily, it made her an incredibly devoted and focused mother. She insisted that I was with her at almost all times. She physically showed me, verbally showed me how important I was to her. She would say, ‘You can never love a child too much.’ As the recipient, I was incredibly blessed.

It does come with a lot of stuff. As a teenager, young adult, that’s not always easy. My mother was a single parent, I was an only child. There’s a lot of guilt you feel wanting to be your own person when your mother is totally devoted to you.

I want our story to be known. I call our story a love story but it’s not all Nirvana. I was a typical teenage daughter and she was a very strict mother.

There were many times when we were driving down the street and I would hope the door would just open and she would roll out into the street. And then please please don’t sing in front of my friends. Don’t do any vocal exercises. Don’t embarrass me.

But that being said, she felt that if you knew how much your parent loves you, that’s gold. And it was gold.

When I look back now on our lives together, I’m so blessed that we both knew how we felt about each other, during our lives. It wasn’t like at the end and it wasn’t after she died that I came to all these realizations. I really appreciated and she too appreciated what we both had. And that’s an incredible gift and blessing.

MN: What would you like people to learn about your mother from this book? What is a common misconception people have about her as a public figure?

I think people think that she was glamorous all the time. She was the complete opposite of glamour. I grew up in Beverly Hills, California. My mother grew up in South Carolina. In Beverly Hills, in 1960, my mother had a vegetable garden, she had chickens and she tended to these things herself. She was out there in the garden, with her hands in the dirt. She was her given name, Eartha. She was as down to earth as you could possibly be. She was the most comfortable connected to the soil and she understood the importance of our environment. She understood that what you put into the earth, you would get back in droves. You put healthy ingredients into the earth and into your body and then beauty comes of that.

Even with human beings, she said, ‘I’ve taken the manure that’s been thrown on me my entire life and I’ve used it as fertilizer.’ And I think that shows the strength that she had to survive. I think a lot of people when you see somebody who stands up on a stage and sings songs like “Santa Baby” or “I Want to Be Evil,” where it’s all about furs, travel and opulence, you assume that way. But she did not at all. In fact, she shunned all those extravagant things. She would say to people don’t give me those things, give me land. They’re not making any more of it.

Source: Pegasus Books / Pegasus Books

MN: I remember in an interview years ago, you said that as you were watching your mother transition, you could tell that she was not ready to go.

Kitt: I don’t think she would have ever been ready to go actually.

MN: Why do you think that was?

Kitt: Well, she didn’t go quietly that’s for sure. She had been sick for a few months. She died from colon cancer. The last few weeks we definitely knew the end was very near. And when she was in the process of passing, she had lost her speech. But she didn’t want to go. She wasn’t going to go quietly.

The hospice nurse said to me, ‘She’s just going to close her eyes and fade away.’ That’s what I expected and it was not what happened.

She left this earth literally screaming, screaming at the top of her lungs.

And I remember thinking in that moment, as horrifying and as difficult as that was, thinking wow, she really was born a fighter and a survivor. They were at the pearly gates, waiting to drag her through and she was not a willing participant.

I remember saying to her, in a very typical mother-daughter way, she’s screaming and I’m screaming back at her.

I’m saying to her, ‘You can go. I’ll be okay. I’ll be okay.’

And the tears were streaming down her face, I knew she understood me. And she didn’t want to leave. And I didn’t want her to leave. But obviously, this was out of both of our hands.

I talk about that moment as sad and as difficult as it is because it’s so real and it’s so who she was. She was so real and vulnerable. What you saw is what you got. I think that authenticity is what her fans and her public got from her. That was an incredible gift we had put on this earth, this woman whose name was Eartha.

You can read more about the relationship between Eartha Kitt and her daugther Kitt Shapiro in the new memoir “Eartha and Kitt” available everywhere books are sold.