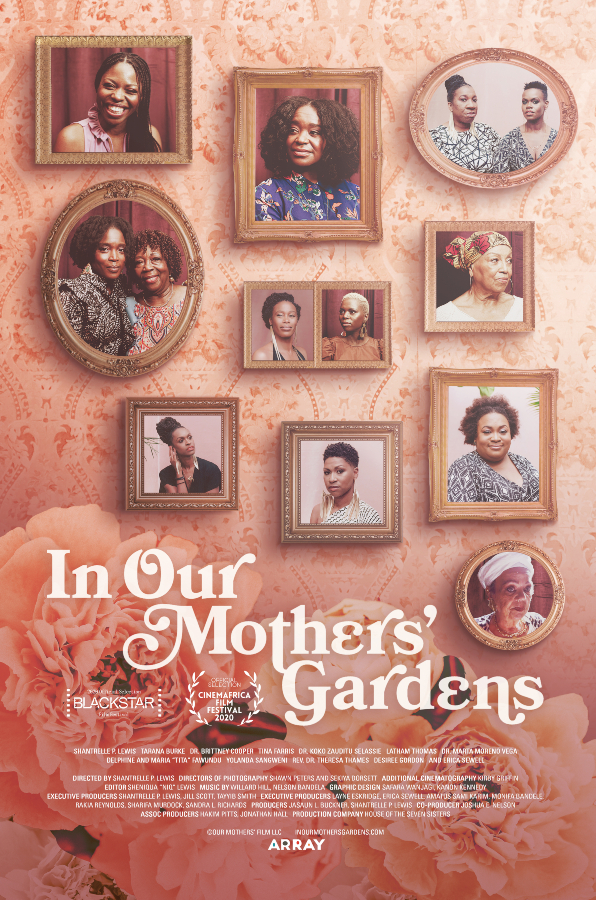

Source: ARRAY / ARRAY

Last week, we told you about the documentary about Black women and mothers, In Our Mothers’ Gardens. This week, we had the chance to speak to the film’s director Shantrelle Lewis before her work begins streaming on Netflix, starting tomorrow, May 6. During our conversation, Lewis spoke about how she prioritized her feminine energy, reconciled with her own mother and listened to the ancestors to get this project made. See what she had to say below.

MadameNoire: How did this project come to you?

Shantrelle Lewis: I had been doing work around self care. I have been doing genealogy since I was a child. My dad was so serious about me knowing our family’s history and legacy.

I always understood that there was legacy in my name, there was legacy in my heritage and there was lots of pride as a Black girl growing up in New Orleans.

Then, years later, I go to Howard and I get introduced to the African Diaspora at large and I’m like ‘Oh my God, Blackness is not a monolith.’

After that time, I was introduced to the Yoruba religion, Lucumí, and that began my journey into African spirituality and calling out the names of our ancestors and understanding how important they are to our everyday life. When people leave this earth, they’re not gone. They’re still with us.

And to be honest, my relationship with my momma, which has been…complicated like many of our relationships with our mothers. You know this person has sacrificed so much for you and loved you so much and would do so much for you, in most of our cases. But there’s still this emotional barrier where you wanted me to be somebody else or no matter what I do, it doesn’t seem good enough or whatever it may be.

I have been engaging in the tough and messy work of unpacking my relationship with momma and her relationship with my grandmother, in the quest to heal and show up as a better step mom for my bonus daughter and to contemplate motherhood for myself. It was a reckoning that I needed to contend with.

MN: If you’re a Black woman with a Black mother, you know that our relationships can be painful but it’s not something we often talk about as a community. So how did you go about getting those stories from the women who were featured in the documentary?

Lewis: I think because I first started to tell my personal stories and my family business, if you will, ten years ago when I curated an exhibit called Sex Crimes Against Black Girls that was inspired by an essay I read. I started putting my business out on the streets. I couldn’t expect the women in the documentary to delve into a topic if I wasn’t willing to go there myself.

There are 22 women in the film and 20 of them are women I’ve been knowing and loving for over 15 years. I knew some of their stories but not everyone. And I think that there’s a level of trust that was already there. Like Tarana Burke, she just came out with a book with Brene Brown, there are certain aspects of her story that I may know about as her close friend. But that’s her work to do. It’s about a level of intentionality and care that I had with their stories.

I approached this in the way that someone who would get a reading from a priest or a priestess would. Someone is pouring out, bearing their soul to you, how do you relate to this person? It was all towards the cause of healing, right. I didn’t want anybody to be re-traumatized in the retelling of their story and I didn’t want to retraumatize myself or anyone in my family either.

So it was with a lot of love and care that enabled me to listen and hold space for people to trust me in such a vulnerable way.

MN: Can you speak to me about the significance of the title? I know it’s an Alice Walker book but why did it feel appropriate for this film?

Lewis: At Howard, I took Black women’s lit. That was required reading. We were reading bell hooks, Alice Walker, Paula Giddings, Barbara Smith, Pearl Cleage, Gloria Naylor, Audre Lorde and I think when I was younger, a lot of these concepts went over my head.

[Dr.] Brittney [Cooper] talks about this in the film, our mothers didn’t always have the resources to go to therapy so their therapy was Iyanla Vanzant books. That’s where they found their therapy. There are a lot of Black feminist texts, I had to come back to as a grown woman, with a blended family, trying to reckon with my own momma.

So when Alice Walker says, “In search of my mother’s garden, I found my own,” I just thought that’s a beautiful metaphor of what is in our mother’s gardens. What did they bury there for sustenance? What did they plant there for sheer pleasure? What did they bury there to hide away? What’s poisonous in their gardens? What are the snakes in their garden? And what seeds can we take to bear fruit in our own? And so, it was just an amazing and beautiful metaphor to me.

Zora Neale Hurston is like my patron saint and fellow Howard alum. In Search of our Mother’s Gardens is where Alice Walker discovers Zora and brings her work back to life. Zora’s work was so instrumental in shaping my identity as a scholar and shaping my practice and my career.

It was a way to give Alice Walker her flowers, which she has many. It was even a way to recognize the relationship between her and Rebecca, it hasn’t always been easy and they’re very public about that.

I felt like it was a great place to start and move the conversation forward, amongst our generation. I feel like we have a lot more tools than our mothers had and of course our grandmothers. We have a lot of privilege as it relates to talking about self-care, mental health and boundaries. We even have language they didn’t have access to.

Source: Gonzalo Marroquin / Getty

MN: I was on your Instagram page and I saw you were reflecting on this process, getting the film made and the recognition that the film has received. You mentioned that your grandmother was instrumental in helping you get this done. How have your ancestors helped in the creation and the execution of this film?

Lewis: Oh wow, how haven’t they? First of all, I was struggling a little in COVID. Just like all of us, we were scared, we were afraid. We didn’t know what we were going to do—I’m going to just be honest with you.

A couple of years ago, there were two readings that I had. One told me that I was going to do a film, related to women and every aspect of the film needed to be of the highest of the highest professional quality because it was going to be on Netflix, I kid you not. They said, ‘It’s going to be on a major streaming platform so everything you do. Everything you shoot, it needs to be of the highest quality.

Now, in my work, my professional work as a curator, that’s how I’m coming anyway. Aesthetics are very, very important to me. I don’t put out work that’s mediocre.

I had another reading that was completely unrelated and was told, ‘You need to be doing work with Black women.’ And my Orisha is Shango, which is a hypermasculine orisha in the Yoruba pantheon. He is the god of thunder and lightening, the King of the Oyo empire in Nigeria.

I’ve always gender-bended in my childhood. I’ve tended to lean toward my masculine qualities and energies, I was always a daddy’s girl and even my body of work, Dandy Lion, that focused on the Black masculine.

So here it is, I’m being told in this reading, ‘You need to be doing work with women and girls because women and girls are the king-makers.’

I’m like chile…can you throw them shells again?! Can we do a second throw?

I find myself obedient—at least I try to be. Because I’m very faithful in my belief system. And with me doing the genealogy work I was doing, the therapy I was doing and having the conversations with my mom, I put my grandmother’s photo up and I tell people she co-directed this film from beyond the grave. I mean this story just poured out. It became divine. I even found VHS tapes that my grandmother was on that I didn’t even know existed. I had no idea. I’m on a tape my senior year at Howard, telling my family at Christmas that I was not going to medical school. I was going to television and film and be an entertainer.

My grandmother, she had a couple of drinks in her already, so she was like, ‘What she said? She said she’s going to be an entertaining what?’

That was also healing during this pandemic. There was so much death around us that I was like really leaning into listening to my ancestors and what they wanted. Also, our collective ancestors.

I keep telling people, the making of this film was not easy but there was a collective song that needed to be birthed through me. I’m only the instrument and this was the tool. There is so much work for so many of us to do. It was beyond me.

So even when times were hard, it was dark, scary and stressful, I didn’t know where the money was going to come from to finish the film, they kept making a way, they kept opening doors, they kept providing. And so all praises due to Gladys Kelvin, Ebiye, my Orisha, my great-grandmother Mama Verna, my grandmother’s cousins Big Nanny and Lil Nanny and to all those maternal ancestors that ushered me into the world and are supporting me in the work that I’m doing today.

You can stream In Our Mothers’ Gardens tomorrow, May 6 on Netflix. You can check out the trailer below.